Swamp Thing #21

Where better to start than at the beginning?

“The Anatomy Lesson” begins with our villain, small time DC villain Jason Woodrue (a.k.a. “The Floronic Man”), gleefully anticipating the death of General Avery Sunderland, a businessman who hopes to research Swamp Thing’s unique physiology and use what he discovers for personal profit. Sunderland hired Woodrue from prison to dissect Swamp Thing’s body, and discover how exactly it functions.

Woodrue quickly runs into some difficulties.

None of Swamp Thing’s organs could realistically function. Woodrue grasps desperately for answers while Sunderland threatens to return him to prison if he fails to reach a breakthrough.

After working tirelessly for 6 weeks, Woodrue finally uncovers the secret origin of the Swamp Thing.

And if Alec Holland is dead…

Sunderland rewards Woodrue’s discovery by promptly firing him, saying “That breakthrough was all that was needed. There are others who can be paid to see the work through to its conclusion.”

But Sunderland fired Woodrue before he had time to explain the most important part…

Woodrue steals control of Sunderland’s computer system, raising the temperature in Swamp Thing’s cell, and locking Sunderland in for the night. Swamp Thing awakens ready to confront Sunderland but finds Woodrue’s report

Now aware that he was never human, Swamp Thing, filled with rage, lashes out at Sunderland, killing him.

Allusions

The title of this issue is an allusion to Rembrandt’s famous “The Anatomy Lesson fo Dr. Nicoleas Tulp” which depicts an “Anatomy Lesson”, a public dissection conducted by a professional for teaching purposes.

Woodrue conducts something similar to an Anatomy Lesson, dissecting Swamp Thing and explaining the body’s function to Sunderland, incorporating the story of the painting into the text.

Also important in Rembrandt’s painting is the use of umbra mortis, the so-called “shadow of death” cast across the corpse’s face, signifying that the corpse was dead.

As Swamp Thing races to murder Sunderland he is mostly seen in shadow, suggesting the umbra mortis is chasing him, hinting at Swamp Thing’s murderous intent.

And sure enough, as Swamp Thing finally kills Sunderland, both are covered in shadow.

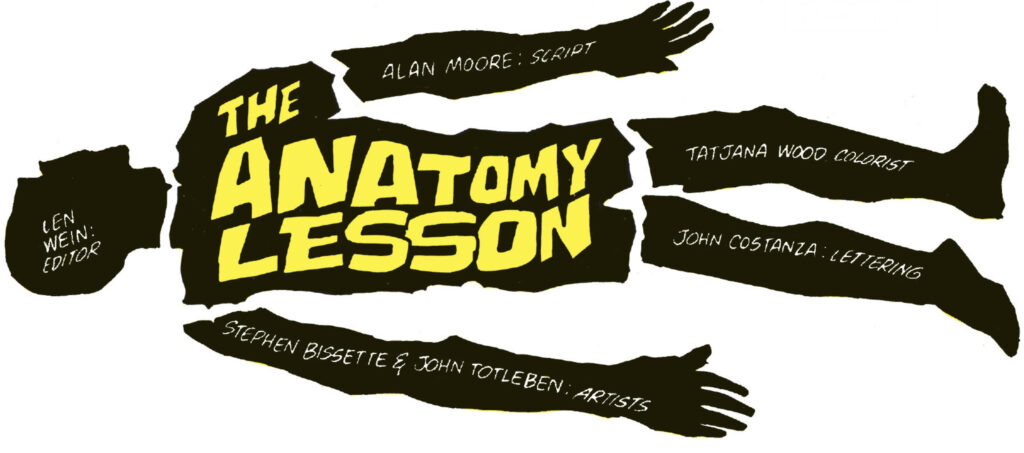

The title card also is strikingly similar to the title card of the 1958 movie Anatomy of a Murder, a seemingly unrelated crime drama. It’s unclear why exactly Moore chose to reference this movie, most likely it’s just an allusion included to add texture to the world, and shout out a film Moore likes.

Moore loves allusion, even if it’s not relevant. In the previous issue he references both Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and Don’t Look Now (1973) (a super weird movie by the way), both of which have no real relation to the story.

These allusions would become more frequent as Moore would continue his career but they are prevalent even at his start with DC comics. Ironically, Moore despises it when his work is alluded to by other writers.

Experimental Art

Around the same time that Moore was tapped to write Swamp Thing, Stephen Bissette and John Totleben excitedly approached DC with some Swamp Thing pages. Like Moore, Bissette and Totleben had big ideas for reinventing Swamp Thing. Their enthusiasm, and lofty goals for the book, landed them a job drawing for Swamp Thing, which, just four issues later, was taken over by Moore.

In “The Anatomy Lesson”, Bissette and Totleben experimented with jagged panels and deep black inking, creating a moody tone with heightened tension. The book looks sketchy and unpolished, with faces and important details often being blurred in excess. The scratchy, engraved-looking art (somewhat resembling Swamp Thing co-creator Bernie Wrightson’s style) sometimes serves to enhance the story, and sometimes creates a frustrating blur. At its worst it becomes slightly annoying to see the details of a scene washed away under Totleben’s heavy inking. However, even with its imperfections, the art always works to tell the story, and the creativity of the artists is easily appreciable.

The team occasionally removed panel borders entirely, instead using repeated images of the same character or object to guide the eye through the page. This technique (commonly called the De Luca effect) is often difficult for artists to accomplish, as it’s important for the lettering and the art itself to provide structure, without the assistance of paneling.

In the below example you can even see Sunderland’s face turn to horror in the metal balls of a destroyed desk toy, a decision that allows time to pass in the story even within a single panel.

Bissette and Totleben also often narrow and tilt panels to reflect changing moods within the story.

Panels will tilt away from their vertical orientation to heighten suspense in a scary or dramatic scene (right), or they may narrow both in size and proximity to a subject to reflect tension building during an exchange (left). This addition of energy to Moore’s wordy and sometimes emotionless script really helps to make the book a more engaging read.

In the left scene the panels focusing on Swamp Thing are in claustrophobic close up, reflecting how Sunderland see’s Swamp Thing. Sunderland’s panels move closer and closer while the physical space they occupy on the page shrinks, implying Sunderland’s impending doom and growing terror.

A standout page is the chase throughout Sunderland’s mansion. Bissette and Totleben had the option to portray Swamp Thing as a lumbering monster running through the halls, but instead they choose dynamic angles and show Swamp Thing’s presence chasing Sunderland through reflection and shadow, creating a page that rewards careful observation, and holds back just enough to make Swamp Thing that much more scary. That extra bit of thought changes a basic chase to a dynamic and tense moment.

Alan Moore and Existentialism

Existentialism is a philosophical theory or approach which emphasizes the existence of the individual person as a free and responsible agent determining their own development through acts of the will.

An existentialist believes that we define ourselves based on the choices we make, that our very being is something we design through our actions. This idea is called self-determinism.

Alan Moore uses Existentialism in his work all the time. Often relating to somebody’s humanity or lack thereof.

In Watchmen, what separates Dr. Manhattan from humanity is his inability to make decisions (he experiences all of time at the same time). He questions whether he is in control, or if destiny shapes his life.

In V for Vendetta, V teaches the value of making decisions based on who you want to be, and the importance of the freedom to make those decisions.

V himself wants to separate himself from humanity to become an idea, thus he hides his face under a mask, his features under a cloak, and makes himself a player in a master plan, a complete servant to Anarchy. By surrendering himself completely to this cause, V loses the ability to betray it, thus enabling him to transcend humanity.

And in Swamp Thing…

Swamp Thing now doesn’t even know if he’s human, so he has the freedom to choose to be a plant.

This newfound freedom for Swamp Thing affords Moore the ability to start Swamp Thing with a blank slate and completely redesign himself (literally and metaphorically). Swamp Thing no longer has to subject himself to human emotion and struggle, he doesn’t even need to breathe.

Moore also tears down Swamp Thing’s belief that he was human. This delusion was keeping Swamp Thing from realizing his true potential, making it impossible for Swamp Thing to be true to himself, and act with integrity.

This story is the revelation that fuels Moore’s exploration of existentialism in the remaining issues of his run.

But why should we care? Why are these themes important?

Because if we choose who we are that means that we are a product of our own actions. We can’t blame any sort of environmental factors or other people for the decisions we make. In existentialism, the judgement we should listen to is our own, and we have the freedom to form our own soul.

Existentialism doesn’t offer a world where we can act whichever way we desire, we must be true to ourselves. Any betrayal to our own integrity is wrong, and if you believe you’re a bad person, by existentialist standards you are.

Now that Swamp Thing is no longer in an endless quest to regain his humanity, Moore can begin a new existential journey, building Swamp Thing up from the most basic decision (“to be or not to be”) to the most complex, exploring what exactly it means to be human (or maybe plant monster).

One response to “The Anatomy Lesson”

[…] inability to recognize reality is something that is stripped away in “The Anatomy Lesson“. Swamp Thing is harshly thrust from the comfort of deception and into the reality that he is […]